Plum Flower Fist- Degrees Magazine, Univ of Regina

This article was originally published by

Degrees Magazine, published by the University of Regina

The original article can be found at

http://ourspace.uregina.ca/handle/10294/3087

Link for French language translation

Plum flower fist

By David Sealy

A University of Regina graduate’s research takes him deep into the vast plains of rural northern China where he studies a once-prohibited folk religion rooted in a unique martial art.

A group of martial arts students are warming up on a field behind Regina’s Miller High School as daylight fades and stars slowly appear. Ray Ambrosi BA (Hons) ’90, BA (Adv) ’94, MA ’00 arrives, carrying three guandaos, or big knives as he calls them. The impressive-looking weapons consist of a wide, curved blade on a 1.5-metre-long pole. Ambrosi greets his students and then demonstrates a few routines with the guandao.

“First we get the beard out of the way,” Ambrosi sweeps his hand under his chin. “This is to pay respect to the god of war Guangong, who had a long beard. Then we bow to the gods, showing more respect, and we begin.”

Ambrosi lunges and thrusts as he twirls the guandao effortlessly in controlled arcs. “This is an iconographic weapon,” he says. “It was used to chop soldiers or bandits on horseback off their mounts.” He turns the heavy knife end over end and explains another advantage to the exercise. “By moving through a large range of motion and breathing properly, this is more than enough of a workout to develop your joint stability and strength.”

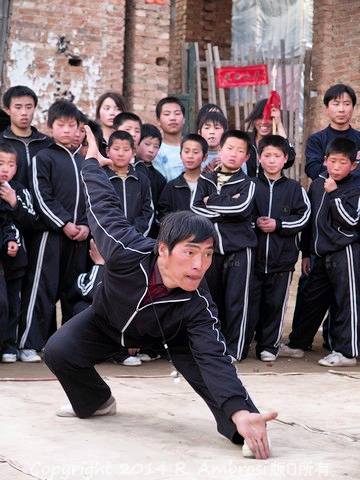

His students are learning meihuazhuang, or “plum flower fist” in English, a martial art that originated in northern China. Not only a form of martial arts, meihuazhuang is a folk religion that provides much-needed social support, healing and spiritual guidance to its practitioners in areas that have been isolated and impoverished for centuries. Ambrosi has spent 10 years in China studying and researching this informal social welfare network.

On his trips back to the West, Ambrosi has spread the word about meihuazhuang’s unique training methods

by organizing seminars and teaching classes. He describes the benefits of training as numerous: improving movement skills and posture, strength, flexibility and clarity of thought. His summer visit to Regina will soon end, and he will return to China to finish his final year of doctorate studies in anthropology at Peking University.

Ambrosi jokes that he initially became interested in martial arts to avoid being beaten up in high school. By the time he graduated from the University of Regina with a degree in cultural anthropology in 1990, he had trained extensively in several martial arts and was an assistant kung-fu instructor at a local school.

Wanting to learn more about Chinese culture, language and martial arts, Ambrosi applied to the University of Regina exchange program and was one of the first students to attend Shandong University in the city of Jinan. There he met Master Yan Zijie, a mathematics professor at the university who also taught meihuazhuang, a discipline that initially confounded Ambrosi. “The first time I ran into meihuazhuang, I was fascinated because it was so difficult. I had no skill in it whatsoever. It was completely contrary to anything I’d learned in martial arts.”

Since the 1950s, the practice of meihuazhuang had been generally prohibited throughout large areas of north China. Nonetheless, in 1992, Master Yan took Ambrosi and other foreign students to a remote and formerly restricted area of northern China to attend a large-scale martial arts festival. Ambrosi notes Master Yan’s objective was to make a political point. The fact that the foreigners were allowed to attend the event indicated that the government’s hard line might soon soften.

At the festival, Ambrosi immediately was “struck by the size –– 10,000 people gathering in one village for a performance. It was noncommercial and very grassroots. The government involvement was minimal.”

The non-competitive nature of the event was also impressive. “There were no winners and losers. There were no two-person matches. There were opportunities for mutual exchange and building friendships. It’s completely contrary to what an exhibition in Canada would be, where the object is to win medals and to beat somebody else up. The sociologist in me realized that there was more going on here than just martial arts.”

Ambrosi explains the borderlands of the vast plains of northern China have historically been a martial arts hotbed. Due to administrative problems and geographical barriers, government exerted little influence. “The land was productive agriculturally, but the border regions have suffered serious natural disasters for hundreds of years. During the Qing and Republican periods, floods along the Yellow River killed many hundreds of thousands. After being struck by a series of natural disasters, the people fell into poverty. Because the imperial governments were not able to control these regions, they became sort of a no man’s Wild West.”

People in the north took measures to organize and protect themselves. “By the late 1900s, bandit armies would come up from Hunan and raid the area. To protect themselves, rural villages formed militias capable of raising an army of 20,000 within a few days.”

Meihuazhuang teachers typically travelled the countryside teaching martial arts skills, which promoted unity between villages. Ambrosi observes that the religious component of meihuazhuang was even more important, stressing the need to respect one’s ancestors and do good deeds. Meihuazhuang teacher-practitioners refuse any compensation for acts of healing or divination. In many rural areas, meihuazhuang is called “The Way of the Poor,” meaning practitioners are not supposed to accumulate wealth and should instead perform good deeds for society.

The tradition of the roving teacher has helped re-establish meihuazhuang in many rural areas. These regions had suffered setbacks during economic reforms that began in the 1980s. Ambrosi says the Chinese government was over-fixated with economic development. “Everything was subordinated to economic growth. There was so much damage to the social structure. In many areas, religious practice, folk customs and festivals were completely wiped out.”

Gradually the government lifted its ban on rural folk religions, realizing that people in the rural regions could help themselves where government could not. The practice of meihuazhuang gave rural people spiritual grounding, showed them how to stay healthy and taught them to care for each other. Ambrosi says that meihuazhuang ritual masters help families cope with missing relatives and other misfortunes. “There’s nowhere else to turn. There’s no government agency to help them. Nobody.

“The ritual masters perform like brilliant social workers and psychologists. They’re helping poor, downtrodden people who have no other means of solving their problems. To give the government authorities a small amount of credit, they are overstretched –– a few hundred police to a million people.”

Ambrosi took advantage of China’s opening doors to foreigners to research and write his master’s degree. His martial arts ability and the great interest in and understanding of rural China gained him unique access to a way of life. “I’d just go into a village and hang out for days and weeks and months. People don’t accept you at first, but your continual presence wins them over.”

The further removal of travel restrictions allowed Ambrosi the opportunity to do field work in Yongnian County. The region was a renowned hotbed of meihuazhuang activity and government repression had been severe and lengthy. “I never thought I’d get to go there. I was a foreigner; I’d stand out like a sore thumb. I’d be hauled off by the police in half a day. I had all my connections in other places, but Yongnian was too fascinating to pass up.”

He established a base in Gucheng village, where town folk had recently built a meihuazhuang temple. He accompanied the local martial arts team as they travelled to other villages to stir up interest in meihuazhuang. “We’d take the team out during Chinese New Year and I would go as cameraman and team member. I would also perform.” Foreigners hadn’t been seen in the region for at least 100 years, “so thousands of people got to know who I was.”

Ambrosi also helped village members approach several Chinese NGOs for support. The end result was the donation of several thousand books and the establishment of a library in Gucheng village.

The north China plain would hold some familiarity to Prairie residents. Villages of one-story houses with tall roofs are surrounded by wheat fields. After the wheat harvest, corn is grown. In growing season, Ambrosi says, “The fields are verdant and beautiful. In the winter, the fields are barren and dry.” Every family farms a piece of land, but family members also engage in wage labour. Small factories, producing items like nuts and bolts and hardware, are often found on the village outskirts.

Village life in rural China is not easy. The air can be smoggy due to industrial activity and coal dust settles everywhere. “The streets are muddy. You’re going to be filthy. There’s no shower and there’s outdoor toilets where you might have to fend off a pig. I’ve been bitten by bedbugs thousands of times. You wake up in the morning and you’re itchy as hell.”

Despite these privations, Ambrosi compiled thousands of pages of field notes and hours of video. Marion Jones, a faculty member in the University of Regina Department of Economics and a member of Ambrosi’s doctoral committee, has a long-term interest in rural China. She and two other colleagues are currently looking at a Chinese NGO’s efforts to establish social welfare services for 200 million migrant workers within the country’s borders.

Jones says Ambrosi’s willingness to immerse himself in the rural culture has produced impressive results. “What Ray is doing is remarkable. It’s only because he is a martial arts practitioner and has been in these communities for years that he has been able to conduct this research at all. It’s a big benefit that he’s an outsider. He’s not an urban Chinese person who the villagers treat with suspicion because he might be a spy. This provides us with a fascinating insight into a very poorly understood culture.”

Back in Regina, the sun has completely set. Ambrosi leads a footwork exercise, stepping from the top of one imaginary post to another. “Don’t just speed through the exercise,” he says to his students, “otherwise your balance will be all over the place.” The students follow suit, their silhouettes moving gracefully through the dark.

David Sealy lives, works and writes in Regina.

Degrees Magazine

NOTE: I’d like to extend my gratitude to Degrees Magazine and David Sealy for giving coverage to my research in 2010. After conducting intensive fieldwork in villages across Hebei in 2006-2010, it was encouraging to return home to Canada that summer and meet with the enthusiastic staff of Degrees Magazine.

You must be logged in to post a comment.