I had been looking forward to hiking in a Saskatchewan parks for several weeks. Having only recently returned from many years living abroad, I was busy with myriad tasks in a new and very much changed Canada, and had difficulty finding time to escape from the concrete and steel confines of urban life.

Natural Environments and Human Health

During the previous eight years, I had been studying and working in Beijing. Although the city is home to many beautiful cultural attractions and natural sites, the levels of air pollution have become so severe that scientists at the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences in a 2014 report deemed Beijing to be nearly “uninhabitable for human beings”. This calamity of pollution has led to heightened awareness among citizens, to widespread support for environmental protection NGOs, and to a tremendous growth in outdoor activities and sports far from polluted urban spaces. While the media has reported widely on the severe pollution in China and India, air pollution is indeed a crisis in urban centers around the world. A Canadian study estimates that even very small improvements in air quality can bring significant benefits to human health, quality of life, and, by correlation, increased human economic productivity.

The desire to spend time in healthy natural environments appears to be ingrained into humans. Emperors and kings maintained large summer resorts to escape from the heat of cities and nature reserves for their pleasure. And even though most of the world’s population now live in urban centers, people’s fascination with rural natural environments has never faded.

While it seems intuitive that that spending time in nature brings a range of benefits to human health, increasing numbers of scientific studies are proving this as well. An article in Scientific American shows how various studies over the years demonstrate that physical and psychological well-being is closely linked to exposure to outdoor environments. Recent research in Japan shows that “forest bathing (shinrin-yoku)”, which means taking walks in the woods, brings many positive health benefits. Evidence suggests that even the scent of forests (and I would suspect other natural ecosystems) can bring about lowered blood pressure, reduced levels of stress and improved performance. It is only a matter of time before the intimate connections between being immersed in vibrant ecosystems and human physical and mental health are unequivocally demonstrated. Government policies will increasingly to recognize the crucial linkages between human health and ecosystems and take action to expand green space and parks.

After having been back in my hometown for several weeks, I was looking forward to a trip out of the spring dust of the city into the countryside. Perhaps as a child, the excursions that my parents took us on got us accustomed to the sensation of walking on prairie grasses in the warm glow of late afternoon light. In China, a trip to the grasslands of Inner Mongolia was like a vivid reminder of Saskatchewan.

Nearly every spring and summer, whenever I’ve been in Saskatchewan, I make a trip to Buffalo Pound Provincial Park. As a child, nearly every weekend, my parents would take us children to a nearby provincial parks for a picnics, hikes and swimming. Even though large algae blooms at Buffalo Pound made the lake not very nice for swimming, we loved going to the park because of the heavily treed picnic area. A small creek ran through the campgrounds and my brother and I enjoyed walking along the dried creek bed and exploring upstream while our parents prepared the campfire and supper. Although we never went to the Nicholle Flats Nature trail as children, sometime in the 1990s, I began making regular summer excursions Nicholle Flats which contains quintessential elements of Saskatchewan landscapes, flora and fauna.

Setting Off

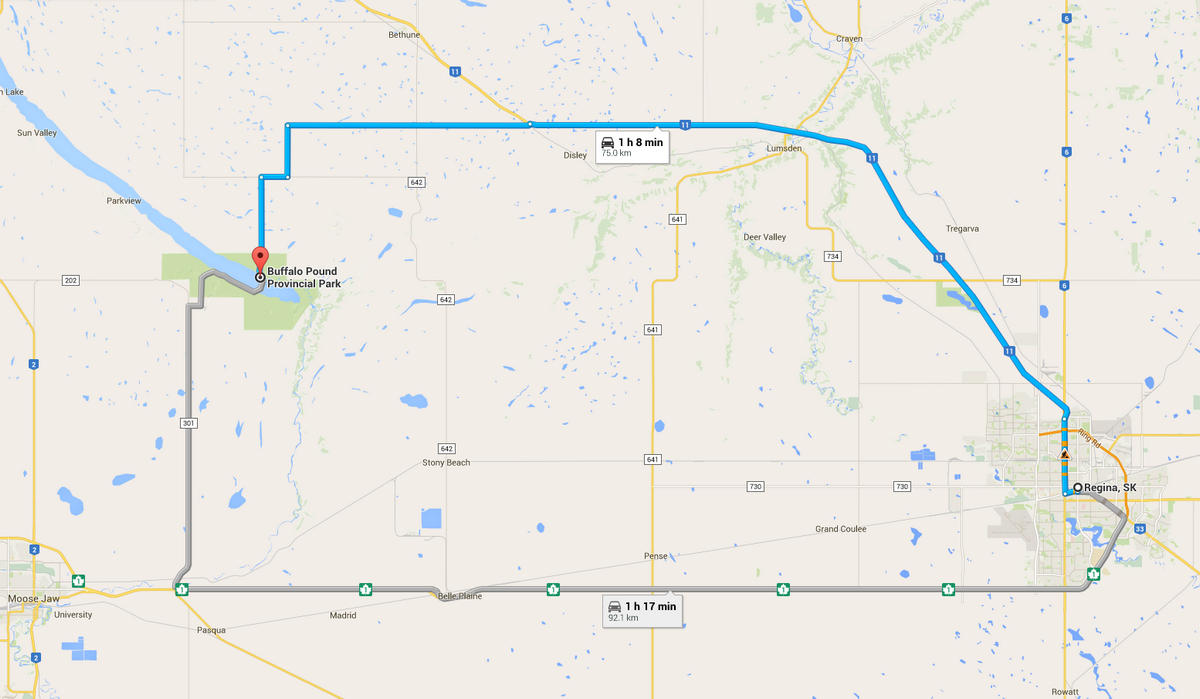

Now, the Victoria Day long weekend in May proved to be a perfect time to make a day trip to a provincial park with friends. Early on Monday morning (May 18) we set off on the 1 hour drive to Buffalo Pound Provincial Park. Stopping at the parks interpretive center at the main gate, we were pleased to find that the entrance fee was waived for the next several weeks. The Center’s staff provided us with park maps and pamphlets about facilities, wildlife and history.

The provincial park established in 1963 is named “Buffalo Pound” to commemorate the traditional hunting methods used by First Nations people who hunted buffalo by using natural topography as a corral or “buffalo pound”. These hunting methods were used by the indigenous inhabitants of the Plains for thousands of years. Buffalo were once extremely common on the Great Plains, but were hunted to the edge of extinction by European buffalo hunters who supplied the commodity market for buffalo hide and tongues. The hunters and other European settlers quite ignorantly thought that the massive buffalo herds, which were so common in the early 1800s, were limitless. Work by conservationists in the 1900s protected the remnants of wild plains bison herds which were then moved to Canada in 1909. These remaining plains bison interbred with northern Woods Bison in Wood Buffalo National Park. Other genetically distinct herds that survived include a herd of plains bison in Yellowstone National Park in the USA. Slowly, the number of bison began to increase.

Leaving the interpretive center, we took a short walk down to the beach. The ice that had covered the lake had broken up some weeks ago, but the water was still cold. A flock of gulls dotting the shallow waters on the sand point began squawking as we came nearer and finally broke into flight.

Some years ago, a group of friends and I found thick beds of fresh water clams on the sand at the beach. Having worked as an archeological surveyor during my undergraduate degree in anthropology, I knew that for hundreds of years, fresh water clams were part of the diet of First Nations people camped along rivers. Many of the archaeological campsites we investigated included copious quantities of clams that had been consumed by people camped in scenic sheltered valleys. My friend and I dove into the slightly murky waters to pick clams and within a short hour had collected a huge basket full and enjoyed a clam feast with friends the next day.

As our group approached the shore, we stood in small groups chatting, and taking photos of the simple prairie lake and brown grassy hills with the comforting sound of water lapping along the shore forming a backdrop against the blue skies. With no one else around to help us take a group photo, we laughed aloud when we found a piece of slotted driftwood. By wedging a smartphone into the notch, the driftwood functioned perfectly as a tripod and we were able to take several group photos. One of the guys joked about how we’d best pack the huge chunk of driftwood along so that we could take group shots while on the trail.

Walking out to the point.

Spotty Raffy chilling by the beach.

Wushu legs enable her to jump high.

With a large chunk of driftwood serving as a tripod, we were able to take a group photo.

Arriving at the gate to the Nicholle Flat trailhead, we sprayed ourselves thoroughly with mosquito and wood tick repellent. A couple and their two children who had set off on the trail ten minutes prior came running back towards the car park as we were preparing to set off. As they swatted insects from their arms and heads, they excitedly explained they had just moved to Saskatchewan from Ontario and had never before seen such huge swarms of mosquitoes. They warned us “Going in there is impossible! You’ll be eaten alive! Just listen to the bugs in the air!” Sure enough by listening carefully, we could hear the buzzing sound of literally millions of flying creatures. While some of the members of our group looked a bit worried, I was not at all convinced that the visible swarms were in fact mosquitoes, or that it would be unendurable.

After we set off down the trail, we soon realized that the insects were not mosquitoes, but another flying insect locally known as “fish flies” that do not bite at all. They did land all over our clothing and get in our hair, but ignoring them proved to be the best solution as they flew off by themselves.

Wood ticks were a more serious concern. Every few hundred meters, we stopped and checked one another for the small horrible little bugs that crawl from grass and shrubs onto mammals. Once they find a warm location, they burrow their heads into the host and feed on blood. While this is certainly most distasteful, these insects are a fact of life in Saskatchewan and must be endured if we are to enjoy outdoor activities during the wood tick season which lasts from March to June. As soon as the weather becomes sufficiently hot, wood ticks die off and no longer present their creepy threat to human hikers and dogs. To guard against wood ticks, it’s best to tuck pants into socks, to wear closed- toe shoes so the bugs cannot get inside, and to wear light-coloured clothing so it’s easier to see the insects. Insect repellent sprayed on clothing helps keep them away.

Our first stop, of course, was to eat lunch in the small covered picnic shelter located near the marsh trail boardwalk. Everyone brought different types of food and we shared tasty sandwiches, apples, shrimp and snacks.

Following our brief but delicious meal, we set off on the marsh boardwalk. Since I last visited in 2008, the old boardwalk had been replaced with a newer and extended boardwalk. I have to say that I preferred the prior version because it was possible to walk along the handrail standing high above the sea of blowing cattails. I was looking forward to walking on the rails again, however the handrails on the new boardwalk, though nicer, are too narrow and are not safe to walk on. It would be far too easy to slip off and fall into the odoriferous mud of the marsh.

Reeds blowing in the wind.

Goofy poses by the girls.

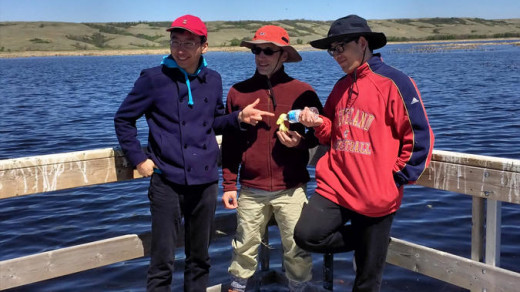

Even more goofy poses by the guys.

Ray perches on the corner of the boardwalk. He didn’t mind sitting on the bird excrement.

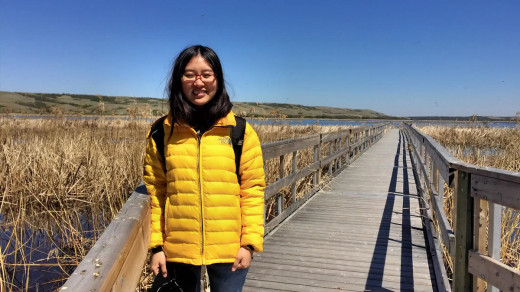

RY on the boardwalk.

After admiring the beautiful lake, ocean of reeds and cattails amidst the sound of the wind punctuated by birdsong, we set off down the trail that runs adjacent to the buffalo preserve. Park staff told us that the buffalo usually graze in this part of the reserve in the morning before the noon heat. Perhaps that is why we didn’t see any of the huge furry beasts on today’s hike. To my surprise, we did not see any white-tail deer either. One year, we spotted dozens of deer during a day hike.

The main trail to the Nicholle homestead.

Checking to admire the view and scan for wood ticks.

Spotty takes a break in the grass.

Marching along the trail

The gently meandering trail along the lakeshore soon led into a wooded area, and then down into a shallow valley area that was flooded by spring meltwater. A young couple with their children arrived at the flooded area several minutes prior to our arrival but now were turning back to return to the parking lot. They explained that spring flooding had left this section of the path impassable, a perspective that the children clearly did not agree with. They encouraged us to continue saying “You can probably make it through the water over there”.

Getting through the flooded area required some careful planning of where to plan one’s footsteps. A false step would result in shoe full of water and smelly mud, but beyond that, there was no inherent danger. Many hikers before us had laid down broken branches and dead wood to function as “stepping stones” or little bridges and passing through the area was really quite fun.

Ray makes his way through the flooded area.

RY enjoys the challenge of finding a path through the flooded woods.

J finds her own way across the little creek.

Everyone makes it across the gloopy mud and out of the flooded-out path area.

After a few short kilometers, we made our way around a curve in the trail and arrived at the natural water spring that lay just a short distance from the Nicholle farmhouse. In years past, after a long hike, I always enjoyed a long drink of the cool spring water to quench thirst after a long days’ hike. This time we hesitated after noticing a sign warning that the water was not fit for consumption and decided to rely on our bottled water supplies. Unlike on previous trips to this spring, there were no frogs leaping through the reeds.

Spring-fed pool at the Nicholle Homestead

We wanted to drink the spring water, but the sign indicated it is not safe.

A field of reeds and catttails blows in the prairie wind.

The old Nicholle homestead lies directly ahead.

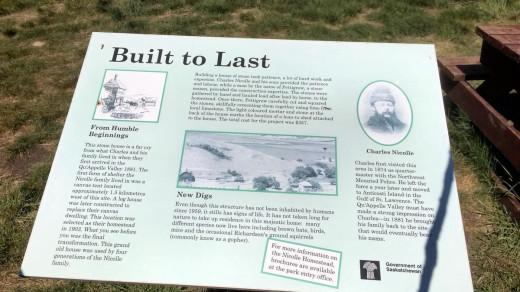

The sign provides a brief history of the homestead.

J takes a photo by the walls of the stone house that has stood for decades.

We stop for a rest at the old stone house.

A hundred meters further on lay the Nicholle farmhouse, an impressive stone structure. Various sources claim different dates of construction. One source states that the stone house and barn were built in the 1880s. But the interpretive sign standing beside the house suggests that the house was built in 1903. Regardless, this impressive house was inhabited by four generations of the Nicholle family until it was abandoned in 1959. Its walls and roof are still firm and solid. I can only hope that one day, a crew of volunteers might work to restore this house to ensure that this part of Saskatchewan’s built heritage will continue to stand as a landmark and as a means by which to commemorate the early settlers of this province.

We walked over to the remnants of the stone barn to wonder over its construction. According to an interpretive sign introducing the barn, the Nicholle family had hoped to raise horses here. But a devastating winter in 1906 led to the death of over 400 horses—a loss which permanently derailed their dream. The barn fell into disrepair and was eventually torn down in the early 2000s. How many years did the family and their friends toil to collect the stone for these buildings, hew it into shape, and painstakingly erect wall and roofs? If you stand quietly and imagine the scene as it would have been in the early 1900s, you can hear the sound of chisels on stone, hammers clanging, the neighing of horses, dogs barking, workers laughing, as the sounds of friends, family and farm resonate from the distant past into the present.

Apparently hungry again from our hike, we set up our secondary snack station on one of the picnic tables near the house, drank from our water supplies, and snacked on chocolate, nuts, and blueberries. A stick that I had been using to clear cobwebs from our path had a jagged split at one end and functioned as a convenient “tripod” for a group photo.

Taking a brief rest at old farmhouse.

Luckily we had chocolate and blueberries.

A short stick we found functions perfectly as a tripod.

The convenient tripod allowed us to snap this group photo.

Nicholle farmhouse from the direction of the barn.

After spending 40 minutes admiring the view and marveling over the stone-masonry of the old house, we decided to set off on our return hike to the trail head. Feeling adventurous, YG and I chose to climb to the top of a tall hill and see if we could walk along the top of the valley for a while before reconnecting to the original trail. The scene from the top of the hill was inspiring– the entire valley lay below us as a vast expanse of intermingled grassy brown and blue hues. Much to my surprise, we were indeed able to find our way back down to the trail in the valley bottom. As we hiked down the hillside, we noticed how the tall grass had smoothly flattened against the hillside. The smooth texture made us want to slide or roll down the hillside in the buoyant grass.

The Nicholle farmhouse from the top of an adjacent hill.

RY rests on the grassy hillside enjoying the view.

After an hour of hiking, we returned to the parking lot at the start of the trailhead. Several other carloads of people had just arrived and were setting off down the same trail. A couple we met on the way back explained they were going around this section of the lake– a trail that would take them 2 hours. Next time, I will also take this round-trip trail and spend more time at this beautiful and simple lake.

During our short Hiking at Nicholle Flats, the seven of us basked under the warm sun, enjoyed the sounds of bird, the scents of prairie grasses plants, and the refreshing coolness of air blowing off the still frigid lake water. Regardless what the scientific studies suggest, our day hiking along the lakeshore and grassy hills enabled us to return to the city feeling rejuvenated and in high spirits.

You must be logged in to post a comment.