Rural Meihuaquan Traditions- Old martial art brings new spirit to rural China 乡村传统- 古老武术令中国农村焕发生机

Villages Meihuaquan Traditions- Old martial art brings new spirit to rural China 乡村传统- 古老武术令中国农村焕发生机

Note: This article was commissioned by the Goethe-Institut and first appeared on http://www.goethe.de/china in November 2013. It appeared on the Goethe-Institut website in German, Chinese and English and can be found at http://www.goethe.de/ins/cn/en/lp/kul/mag/vtr/swl/11980640.html. Chinese and German translations are also provided. I have republished it here in conformance with the copyright contract I signed with Goethe-Institut but have added several additional photos and captions.

Chinese version of the article follows the English version.

Old martial art brings new spirit to rural China

Note: The names of places and people have been changed to protect privacy.

Despite the prolific rural outmigration caused by China’s rapid urbanization, Minghe village in Heibei province is experiencing a renewal of community development and social cohesion that is attributable to the revival of a once-outlawed folk martial art and sectarian religious group, Meihuaquan (Plum Flower Boxing). The social function of meihuaquan activities– increased communal cooperation and an enhanced sense of social responsibility – is helping remedy the critical deficit in social trust and community cohesion that characterizes contemporary Chinese society.

Martial arts and folk religion

Though principally known as a martial art, Meihuaquan is nonetheless also a sectarian religion with distinct initiation rituals and a complex cosmology localized in thousands of villages in over 100 counties throughout North China. Meihuaquan consists of two aspects – a wǔchǎng martial field concerned with martial arts that serves as the “public face” of the sect, and the largely-underground wénchǎng ritual field involved in the worship of deities. However, there is a great deal of diversity in Meihuaquan’s structure and beliefs. In some regions, it is primarily a martial art with little religious influence. In other regions, it has a strong religious focus and the majority of sect members may not practice martial arts at all.

The re-emergence of an underground martial art

Outlawed by Ming imperial edicts that continued until the fall of the Qing, grassroots martial arts and folk religious associations, including Meihuaquan, were nonetheless perpetuated by adherents who concealed their activities for centuries. While culturally important in this region, historical accounts of Meihuaquan are rare because authorities held folk culture in disdain and practitioners remained underground not daring to document their activities.

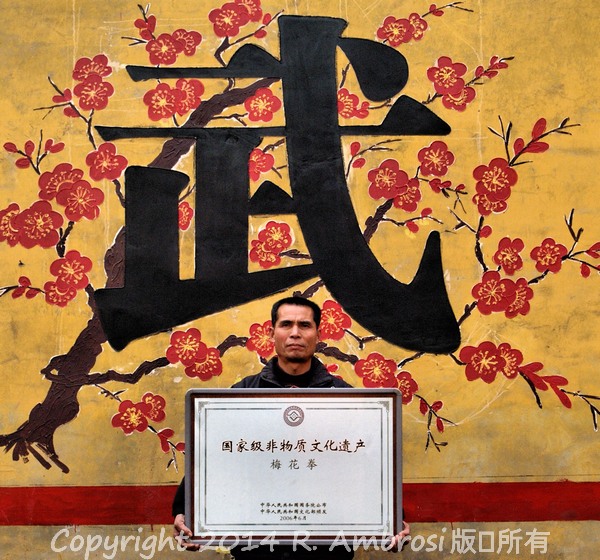

After 1950, regions where Meihuaquan was primarily a martial art were largely ignored by the state and relatively free to practice their fighting tradition. However, regions where Meihuaquan involved religious practice often experienced severe repression. By the late 1980s, the state relaxed prohibitions against Meihuaquan in most regions with the noticeable exception of the Handan city administrative area in Hebei. Owing to historical events in this district, local government engaged in concerted efforts to extinguish Meihuaquan right up until 2006 when the National State Council designated Meihuaquan martial arts as a national-level Intangible Cultural Heritage. Because the state had granted “heritage status” only to wǔchǎng martial arts and had turned a blind eye to underground wénchǎng religious practices, Meihuaquan became a semi-legal entity.

Recognizing the new-found legality of martial arts as an opportunity to reinvigorate Meihuaquan and prevent its extinction, a group of determined organizers in Minghe village quickly rallied the support of members. Within months, they had raised funds and secured government permission to build a Meihuaquan Teaching Center where they began providing free martial arts instruction to rural youth. Because folk religions are forbidden by the state to build temples, the Centre covertly served as a temple for Meihuaquan religious practice.

Building community through Meihuaquan activities

The swift construction of the Centre in 2007– the first in Hebei– signified that Meihuaquan was on the cusp of rapid revival in spite of having been suppressed to the brink of cultural extinction. To observe this process firsthand, I began long-term fieldwork in Minghe village where half of the families are “disciples” or followers of Meihuaquan and only a small number of disciples actually practice martial arts. The construction of the Teaching Centre rallied support of disciples in the village and vicinity and was instrumental in rejuvenating wénchǎng religious traditions, and wǔchǎng martial arts training and performances that form family, group, and inter-village linkages. The Meihuaquan community is led by wénchǎng ritual specialists who follow sect conventions that explicitly prevent the concentration of decision-making power and emphasize consensual decision-making– traits that quickly garnered community respect and support.

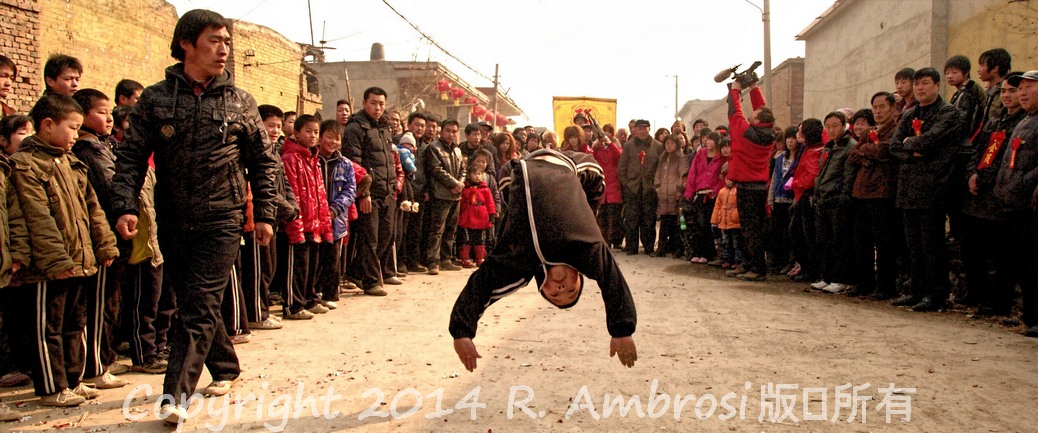

Immediately upon opening, Teaching Centre leaders voted to offer free martial arts classes. Within days, hundreds of youth began training and within months the village martial arts team was performing free demonstrations in villages throughout the region. Each night the Centre became a hub of wǔchǎng martial arts and wénchǎng religious activities involving young and old. The temple courtyard is the site of wǔchǎng martial arts activities- the “public face” of Meihuaquan. Over one hundred students practice in the courtyard while parents and grandparents gather to watch. Their coach, well-known for his martial arts and teaching skills, commutes daily to teach free of charge in accordance with Meihuaquan codes that forbid monetary or gift exchange and thus prevent the commodification of sect traditions.

Meanwhile, a range of Wénchǎng activities are enacted inside the Centre. Meihuaquan believers kneel at the shrine to thank deities and appeal for divine intervention for concerns ranging from family stability and happiness and recovery from sickness, to safe travel and stable employment for sons and daughters working as migrant labourers in far-off urban centres. Another group of believers consults with divination experts, while others gather around the TV to discuss Meihuaquan’s development and watched videos espousing Buddhist and Confucian moral education. These activities pause for an hour while a large group gathers to chant scriptures. This predominantly female group was established by several women who sought out elders able to teach traditional scriptures and melodies shortly after the temple was built. Melodic chants praising folk deities and asking for protection drift into the courtyard and instill a sense of the sacred to martial arts training. For the first time, there is a central site where disciples can gather as a community and provide communal leisure activity for youth, women and men. The range of activities engage believers, attract new adherents and rejuvenate interest among families that had previously adhered to the Meihuaquan faith but had abandoned it during the decades of repression.

Many village children learn Meihuaquan beliefs through practicing martial arts. Before each practice, students kneel to Meihuaquan deities and recite the sect’s moral codes. While the students are trained under one main teacher, in accordance with Meihuaquan traditions that encourage studying from several masters, they also learn from other practitioners and elders. Within months of its establishment, the village’s martial arts team began performing throughout the county at festivals ranging in size from small local celebrations, to intra-village exhibitions attended by thousands of spectators. The performances delivered an implicit message that Meihuaquan was no longer suppressed, and that a Teaching Centre had been approved by the government. These events also provided network building opportunities where young martial artists met counterparts from other villages and expanded their social world far beyond what would be possible had they not practiced martial arts. Sect leaders also renewed historical relationships and made new alliances with hundreds of other disciples in villages, towns and cities distributed over several provinces.

A force for communal change

Corrupt, untrustworthy and ineffectual village government, exacerbated by the lack of alternative forms of civil society leadership in the community, resulted in serious degradation of public infrastructure. After the third year of the Center’s operation, the broad social respect it had garnered by virtue of efforts to re-popularize Meihuaquan empowered leaders to undertake projects to enhance community welfare. They began with smaller efforts such as digging water wells and sending martial arts students to clear snow from village roads and check on elderly shut-ins after winter storms. Lauded by the community, they began larger projects to improve the village’s education system and built a library with NGO support. A year later, they completed construction of a not-for-profit elementary school. Long aware that the village’s notoriously poor roads were a hazard to the elderly and an impediment to local industry, they led efforts that paved the majority of village roads– the first material improvement in public infrastructure in over a decade.

Conclusion

Decades of repression prevented Meihuaquan from serving as a community group active in public life. This began to change when the Centre was established as a hub for activities that united disciples in cooperative labour and a sense of mutual purpose. Martial arts performances in the district connected the village to distant settlements, enhancing the villager’s sense of belonging to a larger community defined by shared aspirations to improve society. Once the Centre had accumulated sufficient social trust among disciples and the community at large, it assumed characteristics of civil society and Meihuaquan disciples began the shared work of implementing projects that benefited the entire community.

The resurgence of Meihuaquan’s religious beliefs and martial arts jointly play a crucial role in rejuvenating the aspects of leisure, social integration, cooperation, community spirit and social trust that were fractured by centuries of government policy outlawing grassroots organizations and denying people access to the traditional institutions through which they could participate in public life and achieve a sense of belonging and dignity. By embracing community-minded projects that work towards building a sense of social responsibility rather than the pursuit of capitalistic profit, Meihuaquan in Minghe village has assumed an important leadership role in both the generation and sustenance of social trust and the expansion of the public sphere.

END

Author: Raymond Ambrosi .

After working in government and at research institutions in Canada, Raymond Ambrosi attained his PhD in Anthropology from Peking University. Phd research on folk religions, civil society and community development included living in Minghe village for two years. His Geography Master’s thesis on cultural tourism examined the role of folk martial arts in sustainable rural development. Later work in Japan focused on religious festivals, folk martial arts and community cohesion. He is currently a researcher, consultant and writer based in Beijing. Hobbies include, naturally, martial arts, photography, videography, yoga and various exercise modalities.

古老武術令中國農村煥發生機

在中国城市化浪潮的背景下,大量农村人口选择外迁。然而,河北省洺河村社群却焕发生机,社会凝聚力不断增强。洺河村的复兴归因于一度被查禁的民间武术和宗教团体——梅花拳的复兴。

虽然梅花拳主要被视为武术拳种,但它还是一个民间道门,其入教仪式颇具特色,信众的宗教信仰体系与世界观错综复杂,在华北地区100多个县的数千个村庄广泛流传。梅花拳由武场和文场两部分组成,武场关乎武术,是梅花拳的门面,文场敬祖师拜神灵,大部分活动不对外公开。然而,梅花拳的结构和信仰变化万千。在一些地区,梅花拳主要作为武术派别而传播,其宗教影响力甚微。在其他地区,该拳种则具有浓厚的宗教色彩,教派成员大多从不习武。

地下武术再度兴起

明朝曾颁布诏书,下令查禁包括梅花拳在内的民间武术和宗教团体。这一状况一直持续到清朝瓦解。然而,几个世纪以来,大批梅花拳追随者进行秘密活动,民间组织和宗教团体才得以长存。在华北地区,梅花拳具有重要的文化地位。然而,由于官方曾长期认为民间文化是低俗的,民众只能秘密活动,不敢记录活动内容。因此,如今鲜有关于梅花拳的历史记载。

1950年后,国家对梅花拳主要作为武术形式流传的地区采取不干预态度,这些地区的民众能够相对自由地练习梅花拳。然而,将梅花拳纳入宗教活动传播范畴的地区普遍遭到严重压制。20世纪80年代末,国家放松了对多数地区梅花拳传播的禁止。但河北邯郸地区*是一个尤为明显的例外,由于历史因素,当地政府严厉打压梅花拳活动,迄至2006年国务院宣布梅花拳为国家级非物质文化遗产为止。由于国家仅授予武场文化遗产地位,对作为文场的秘密宗教活动采取不提倡不反对的态度,自此梅花拳游走在半合法的边缘。

洺河村一批意志坚定的组织者认识到,武术重获合法地位,既防止了梅花拳消失,又为梅花拳的复兴带来机遇。他们很快得到当地梅花拳信众的广泛支持。短短数月内,这些组织者筹集资金,获得政府批准,兴建了梅花拳教学中心,开始向农村青少年免费教授武术。由于国家禁止民间宗教团体修建庙宇,教学中心秘密充当梅花拳组织举行宗教活动的庙宇。

通过开展梅花拳活动建设小区

2007年,河北省首个梅花拳教学中心在洺河村很快落成,标志着曾一度遭受压制,在文化层面濒临消亡的梅花拳进入迅速复苏的发展阶段。为了解整个过程,笔者实地考察,进驻洺河村,开始进行长期的民族志田野调查。在洺河村,大约百分之五十的家庭都是梅花拳弟子或拥趸,但仅有少数弟子真正习武。教学中心的建设工作得到该村和周边地区梅花拳弟子的大力支持,对重振梅花拳文场宗教传统、武场武术培训和表演起到了重要作用,并且,在这个过程中形成了各个家庭、团体、村庄之间互相联系的纽带。梅花拳社群由遵从宗派“老规矩”的文场老师领导,宗派“老规矩”当中防止决策权集中,强调集体决策这些主张很快得到社群成员的尊重和认同。

教学中心开业后,中心领导通过投票决定开办免费武术班。短短几天内,几百位青少年参加了培训。几个月后,洺河村武术队开始在当地各村作义务演出。晚上,教学中心成为武场武术活动和文场宗教活动的大本营,村中老少踊跃参加。寺庙庭院是武场武术活动举办地也是梅花拳的门面。一百多名学员在院内习武,他们的父母和祖父母则围在一旁观看。学员们的武师以武术水平和教学技能而知名。武师每天前来教学,不计回报。梅花拳的教理禁止金钱和礼品交易,防止宗派传统商品化。

与此同时,教学中心内进行一系列文场活动。梅花拳信徒跪在神龛前,感谢祖师和神灵,祈求他们保佑家庭幸福安康,病人康复,远在城市打工的子女出行安全,工作稳定。另一群信徒请教占卜师,其他人则围在电视前,讨论梅花拳发展状况,观看有关佛教和儒家道义的教育视频。随后,活动暂停一小时。在此期间,众多信徒聚在一起诵经,这些信徒以妇女为主。庙宇建成后不久,几名妇女找到能够教授传统经文和歌曲的长者,成立了诵经小组。旋律优美的唱经颂扬民间祖师和神灵,祈求保护,弥漫整个庭院,给武术培训增添了神圣感。梅花拳弟子第一次拥有中心场所,能够聚集在一起形成一个社群,为男女老少举办公共休闲娱乐活动。中心的活动范围广泛,吸纳众多信徒参与其中,吸引新加入的追随者,同时重新唤起众多家庭的兴趣。这些家庭过去曾坚持梅花拳信仰,但在梅花拳被压制的数十年间被迫放弃。

在洺河村,许多孩子通过习武了解梅花拳信仰。每次习武前,学员们跪拜祖师,诵读梅花拳教理。学员们由一位主教教师培训。根据梅花拳鼓励多方拜师的传统,他们还向其他习武者和长者学习。中心成立几个月后,村里的武术队开始在全县进行节庆演出。演出规模不一,小到村里的庆祝活动,大到数千观众参加的跨村表演。武术队的演出隐含了这样的信息:梅花拳不再受到压制,教学中心已获政府批准。演出活动还为青年习武者结识其他村的习武者以及扩大社交圈提供了宝贵机会。如果不参加习武,他们可能不会有这样的机会。教派负责人也加深了与老朋友的情感联系,并且与来自几个省的村镇和城市的数百位弟子建立了新关系。

共同改变的推动力

由于存在腐败行为,村政府一度丧失民心,形同虚设。加上当地社群缺乏其他形式的公民社会领导集体,导致公共基础设施严重损耗。开始后头三年,教学中心在复兴梅花拳方面作出的努力赢得社会广泛信任。教学中心领导得以获权开始实施社群公共福利项目。他们首先开展小规模工作,例如掘水井,在暴风雪后派习武学员清扫村中道路积雪,看望被困家中的独居老人。在这些工作得到大部分村民的好评后,教学中心负责人开始进行大型项目,在非政府组织的支持下建了一座图书馆,并为本村小学提供免费武术课,派志愿者修缮学校公共教学设施。一年后,他们又建成了一所公益小学。梅花拳组织者很早就意识到洺河村广为人知的破旧道路是老年人出行的一大隐患,并且不利于当地工业发展,为此,他们发动各方力量,承担了村中大部分道路的修缮工作。这是过去十几年来,该村公共基础设施首次得到重大实质改善。

受几十年被压制的影响,梅花拳一度未能成为活跃在公共生活领域的社群团体。教学中心的成立,为梅花拳及各类活动的举办提供了活动场所。活动期间,梅花拳弟子相互协作,心怀共同目的。武术队在这一地区的武术表演将洺河村与更远的村庄联系在一起,增强了村民们在一个更大的、怀有改善社会的共同愿望的社群里的归属感。在教学中心充分赢得梅花拳弟子和整个社群的社会信任后,梅花拳组织彰显出公民社会的特征,并且,梅花拳弟子开始共同实施一些有益于整个社群的项目。

通过草根组织和传统习俗制度等渠道,民众能够参与公共活动,产生归属感和尊严感。然而,几个世纪以来,政府不断颁布政策,下令查禁草根组织,严禁民众接触传统习俗制度,对民众休闲娱乐、社会融合、相互合作、社群精神以及社会信任等造成破坏。如今,梅花拳宗教信仰和武术重获新生,对这些领域的复兴起到了至关重要的作用。通过开展旨在为社群谋福利和增强社会责任感而非追求经济利益的项目,洺河村梅花拳活动在建立和维系社会信任以及拓展公共领域方面承担了重要的领导角色。

安瑞德(Raymond Ambrosi)

加拿大人類學家。曾就職於加拿大政府和研究機構,獲北京大學人類學博士學位。研究方向:民間宗教、公民社會、社區發展。曾在洺河村生活兩年。現擔任研究員、顧問及作家,常住北京。

You must be logged in to post a comment.